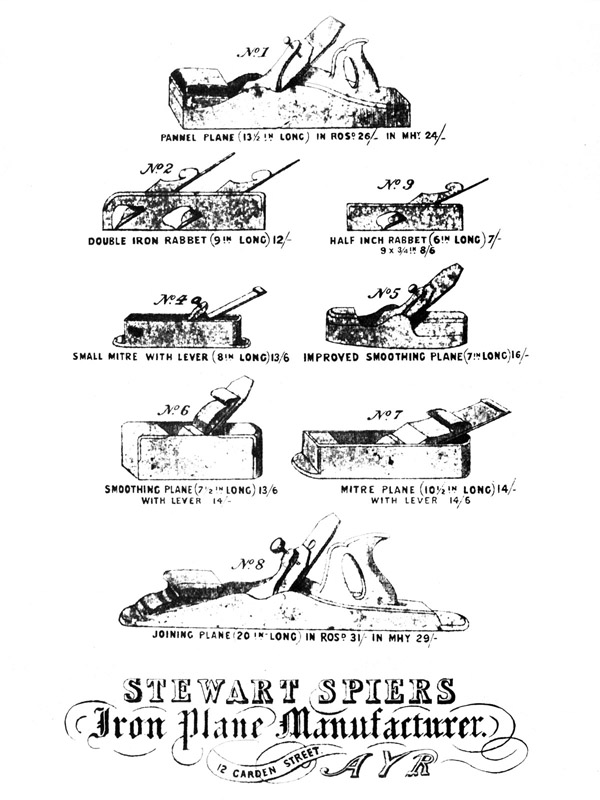

Above is a Spiers brochure/price list dating from somewhere between 1851 to 1858 (sourced from Nigel Lampert’s book), based on the address of the firm at 12 Garden Street, Ayr. Interestingly, most of the bench planes are already available by this time – the only noticeable omissions being the handled smoothing planes and the improved mitre plane. What is not offered in this list are some of the smaller planes – shoulders, chariots, thumbs and bull-noses, as well as the cooper’s plucker.

Some of the numbering has been shuffled about. The joining plane – noted in later catalogues as the No. 2 – is listed here as the No. 8. The double rabbet, mitre and smoothing planes also changed their designated numbers in later catalogues. The numbering system used by this website is mostly based on the 1909 catalogue.

As can be seen in the price list, panel planes (noted as pannel planes) and joining planes are of the first style, featuring the “camel hump” side profile design. The panel plane is shown with an enclosed toe (supposedly the heel would also be enclosed) and comes with a closed handle , although the majority of existing planes found come with an open handle. Much has been said by collectors on this subject, but I’m not exactly sure what all the fuss is about. After all, with such limited space available on the brochure, it would be a waste if both open and closed versions of the same plane were shown. The lever caps are also slightly different – the screw head of the panel plane being much smaller than the one on the joining plane – but no one is making a fuss of this at all. It should be understood that the planes illustrated are an artist’s representation of the planes available in the Spiers range, and should not be considered as exact duplicates.

Both the panel and the joining planes are available in either Rosewood or the (slightly) cheaper Mahogany. It’s not known if the other planes were available with Mahogany infills but Spiers noted in later catalogues that planes could be made to order or to any pattern desired.

Smoothing planes were available in original style (block style) and “improved” versions, but both types were unhandled. No information is given as to the cutter widths available, though the length of the planes is noted. To my knowledge, the “improved” style is a Spiers original design, and I know of no other similar styled planes – as far as side profiles are concerned – before this time.

Mitre planes are also of the original, box style, design – a style not created by Spiers but one which had already been in use for some 50 years or so. Interestingly both a wedged version – as shown in the larger mitre – and a levercap version are available. Again, there is no information given as to the cutter widths.

Finally, both types of rabbet planes can be seen in the brochure, including the Spiers-designed double iron rabbet plane – a plane which obviously sold in enough numbers to warrant its inclusion right up to the 1930 catalogue. It also seems apparent that two irons were supplied with the plane even as far back as this price list. While there is a cutter width for the 9 inch “ordinary” rabbet plane (¾), none is given for the either the 6 inch or the double rabbet planes – though it can be assumed that the 6 inch would have a ½ inch cutter and the double would have two ¾ inch cutters like its single-iron cousin. Indeed most of the earlier double iron rabbet planes found have been ¾ wide.

There is one last thing I should mention in regards to this price list. It’s something that I’ve not heard anyone else mention before, but the prices for these planes is quite high – especially when you compare them to the prices given in the 1909 catalogue. For instance, if you look at the 13½ Rosewood infill panel plane, there was only an increase of 4d in the 50-60 years from the 1850’s price list to the 1909 catalogue (26/- to 30/-), but by the 1930’s catalogue – only some 20 years later – the price had doubled to 60/-. It’s a very similar story for the other planes featured in the range.

I have several theories for this, any of which may, or may not, be true.

The first is one of labour. Early on in the business it would have just been Stewart Spiers making the planes. There is a limit to the amount of work he was able to complete in any one day, but a certain amount of planes would still need to be sold each month to provide Spiers with a living. Now it’s been said that Spiers would have continued on with the cabinetmaking aspect of his business – especially during lean times – but, personally speaking, I’m not sure that this would’ve been the case. I say this because making dovetailed infill planes, by hand, can be quite time consuming. For example I think the fastest time that I could make a panel plane was 3-4 days from start to finish. I would have to go back over my time sheets to be sure of actual hours worked but, from memory, that seems about right. It would also be interesting to see what Konrad Sauer (of Sauer + Steiner Handplanes) would have to say about this, and I might ask him one day.

I figure that if Spiers ever had much in the way of any “down-time” then that’s when he would start working on a new plane design. That’s what I would’ve done anyway. Before long you would have 8, 10 or 12 different designs – all of which you would need to have “showroom” examples of by the way – and you would simply be too busy to consider other work, cabinetmaking or otherwise. If there’s only one person doing all the work, and the work is very time consuming, then this has to be reflected in the finished price of the plane. Taking on extra workers – even if its just to do the more menial work – can help to lower the costs of the finished planes.

The second theory is competition. Spiers may have found that he needed to lower the prices of his planes because there were now several other manufactures making similar-styled infill planes – Makers such as Thomas Norris, Mathieson & Sons, E. Preston & Sons, Henry Slater and Marples & Sons, to name a few. Initially I believe Spiers supplied most, if not all, of the metal infill planes to Mathieson, as he did with a number of retailers. For instance I think the planes shown in the 1875 and 1887 Mathieson catalogue are actually Spiers-made planes that have been “badged” for retail by Mathieson, and have not been made by them at all.

However, after a while Mathieson, and other makers, began manufacturing their own versions – possibly because Spiers couldn’t keep up with the demand – but definitely because their own profit margins could be increased. Once this stated happening Spiers may have been compelled to drop his prices to remain competitive.

A third theory is one of material costs, though I don’t really believe that this would have been as much of a factor in determining prices as the first two. Yes, with an improving transport infrastructure and the far reach of Victorian Britain in terms of availability of goods, the prices for rosewood, iron, steel and gunmetal may have dropped somewhat – but not enough to significantly lower the prices of the finished planes.

If anyone out there has any theories or thoughts of their own on the matter I would be interested to hear from you.